Urpflanze street Plants, Museum of Economic Botany

by Lisa Slade

I’ve been collecting and documenting ‘volunteer’ plants, as my mother calls them (most people would use the term weeds) from along streets and walkways since 2011. I select an area that is approximately 5 metres square and pull up the plants, roots and all, from that vicinity. I then record the location and the date of collection, with these details becoming part of the title for the work of art.

Caroline Rothwell’s description of her process of plant collecting has much in common with the garden-variety botanist: careful removal of the sample, citation of the date and location, and even the mounting and labeling of the specimens. Rothwell’s collecting however, is neither underpinned by research (at least not of the botanical kind) nor by the desire for cultivation. Through each act of collection and collation, she is creating a new class of plant – a überplant. She’s playing God… or at least Goethe.

With the plants from each street location collected and amassed to form a super-weed, Rothwell is referencing Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s theory of the archetypal plant, published in The Metamorphosis of Plants in 1787. Goethe imagined a system whereby the emblematic ‘die urpflanze’ represented all of the possibilities for both existing and imaginary plants. In Goethe’s words,

The Primal Plant is going to be the strangest creature in the world, which Nature herself shall envy me. With this model and the key to it, it will be possible to go on forever inventing plants and know that their existence is logical; that is to say, if they do not actually exist, they could, for they are not shadowy phantoms of a vain imagination, but possess an inner necessity and truth.[i]

Goethe’s theories seem fateful premonitions of modern-day investigations into hybridity, bio-mimicry and genetic technology. This new, über science with its malevolent and utopian potential, combined with Goethe’s more than 200 year old theories, have informed Rothwell’s Urpflanze street plant series, exhibited here in the auspicious context of the Santos Museum of Economic Botany.

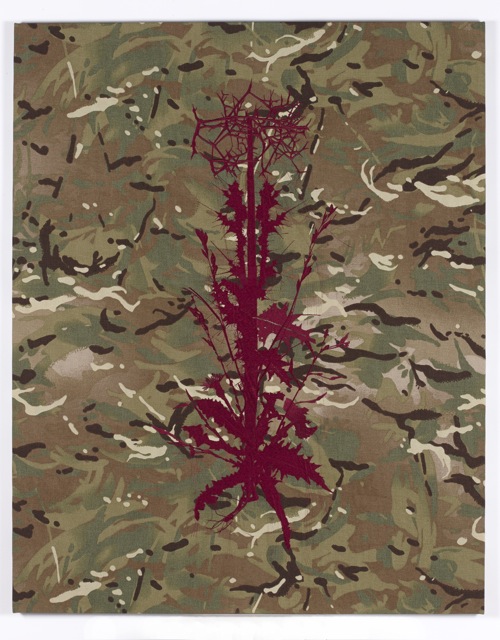

Some of the über plants are ‘drawn’ in embroidery onto camouflage backgrounds, with each camouflage pattern providing the geo-political context for the place of collection. For example, Ben Quilty collected and documented weeds whilst in Tarin Kot, Afghanistan in 2011 as Australia’s official war artist. Using 171,700 stitches the weeds collected by Quilty are recreated onto the Multi Terrain Pattern (MTP) worn by Australian soldiers at war in the region. Military camouflage imitates the local environmental – taking its cues in both colour and shape from the endemic botany.

By choosing to use camouflage (a word that’s usage originated during world war one) Rothwell alludes to the rarely considered colonisation of the natural world that occurs during war. By choosing to preserve ‘weeds’, commonly defined as plants that are out of place, she also alludes to the territorial intrusion that occurs during war. According to British curator and art historian Nicholas Alfrey,

By matching the weeds to the military camouflage of the country in which the weeds are collected, the conversation extends into explorations of borders, colonisation, industrialisation of the environment, invasion of eco-systems etc. The works are also a painterly form that looks to the feminine art of embroidery, presented here as industrial and militarised.[ii]

Put more simply by the artist herself, “I see plants as paralleling how humanity travels. Where we go they follow. Like us, they are exceptional colonisers”.

Lisa Slade, Project Curator, Art Gallery of South Australia

[i] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey: 1786-1788, translated by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, New York, 1968, pp 305-6

[ii] Nicholas Alfrey, The Weeds of Arcadia, 2003. http://www.carolinerothwell.net/writing/the-weeds-of-arcadia

[1] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey: 1786-1788, translated by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, New York, 1968, pp 305-6

[1] Nicholas Alfrey, The Weeds of Arcadia, 2003. http://www.carolinerothwell.net/writing/the-weeds-of-arcadia